As I worked on last month’s Part 2, I considered just how far I could expand this story, or, put another way, how much more readers would tolerate. In this concluding post, I want to take a brief look at how the South handled the same supply problems that winter, as well as how they aggravated the problems for the Union cavalry. Unfortunately, corresponding records do not survive for the Confederacy, certainly not in the vast quantity we have for the North. Suffice it to say, the South faced the same weather, the same mud, and longer supply lines with fewer resources. Moreover, Lee could not be supplied via a water route, as the North supplied the Army of the Potomac. Thus, Lee and Stuart needed to find other solutions.

Following the Christmas Raid, Jeb Stuart and Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton remembered at least one key result of the raid differently. Hampton, who wrote his report on January 5, 1863, said of his horses, “I regret…that I lost several of my horses, broken down by the long march, and that very many of them are rendered unfit for service from the same cause.” Stuart, writing his report 13 months later, noted how Union cavalry had been “crippled,” while claiming his own command had “returned in astonishingly good condition…” Who to believe?

On January 27, General Lee had acknowledged to one of his cavalrymen that “provisioning this army is becoming one of much difficulty.” Lee maintained a picket line every bit as long as Hooker and Stoneman, but aware that he could not provide forage as needed, Lee allowed Stuart to rotate his men off the line, dispersing them to areas where they could recuperate and enjoy abundant forage. I believe Lee also used his infantry for front line picket duty more than the Federals, though Burnside and Hooker maintained an inner picket line manned by infantry, as well as posting infantry along the river around Falmouth and Fredericksburg.

In spite of their supply problems, Lee and Stuart found ways to prevent their opponents from obtaining significant rest or recuperative unsaddled time by continually harassing Union pickets. In addition to raids across the Rappahannock River, such as the dash that resulted in the fighting near Hartwood Church, Southern troopers based on the northern side of the river proved as effective in their operations against the Union lines as John Mosby would soon be in Northern Virginia. Men from the 4th Virginia Cavalry, the Iron Scouts from the 2nd South Carolina Cavalry, and other units, all less well known than Mosby and his eventual battalion, made near daily forays against picket posts and the telegraph line. Their actions forced Stoneman to maintain daily patrols along the army’s line of communication, and other avenues. Thus, even when Stoneman’s horses and troopers were not standing watch at the front, they may have been marching through snow, rain, and mud.

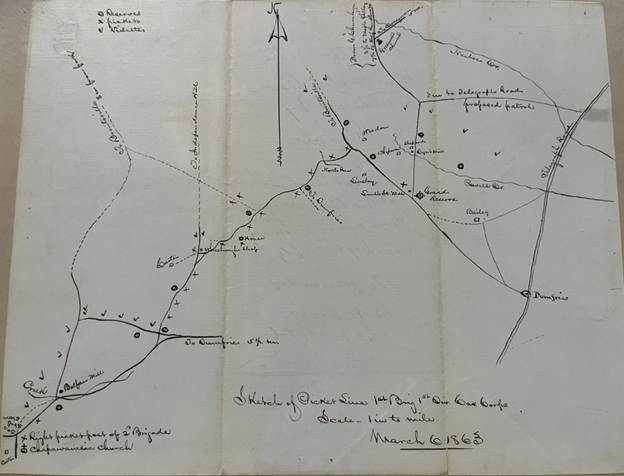

The Union picket line, as presented last month, remained in constant flux, moving in and out as events dictated. I have never seen a contemporary map of the entire line but a few maps, covering sections of the line survive. The map I created with Julie Krick and presented last month is a general approximation of the line as it existed for a period of time in February and early March 1863. The changes in the line would have, at least in most cases, been minor adjustments and I believe the map serves well for the period of the army’s winter encampment.

Many years ago, before digital cameras, smartphones and scanners, the only easy means of reproducing documents at the archives was the faithful old Xerox machine. But those copies do not work well today, so I recently went back to photograph some key items, including a couple Union picket maps of the line to the north and west of Dumfries. The two maps represent the line held by Col. Benjamin ‘Grimes’ Davis and his 1st Brigade, of Pleasonton’s 1st Division, on March 6, 1863, and March 14.

Near the top of the March 6 map above and just to the right of center you see Greenwood Church. Completed in 1855, the church sat very near the modern intersection of Minnieville Road and Cardinal Drive in the Dale City area of Prince William County. Burned during the war, a newer church stands today nearby. Just north of the church, off the map, is an area known then, though less so now, as Maple Valley. The Iron Scouts prosecuted their hit and run war as far west as the Blue Ridge and often joined with John Mosby on his raids, but their Confederacy during the winter, as opposed to Mosby’s, was the area bounded by Greenwood Church, Maple Valley, and the town of Brentsville to the west. This was an extremely dangerous area for unwary Union soldiers and may explain the lack of detail in that area on the map.

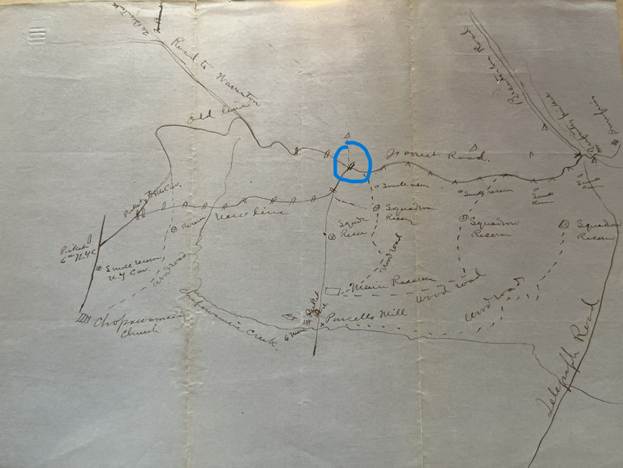

This second map depicts nearly the same area, one week later on March 14, with only a slight difference in orientation. I believe Davis had his men picketing the Dumfries Road, modern day Rt. 234, on both maps. At Independent Hill (circled), the main line then appears to bend south and follow modern Aden Road. You see the notations regarding an old line and a new line west of Independent Hill, where Davis may have maintained a lightly manned picket line between the Dumfries Road and Aden Road and then withdrawn it.

On the eastern half of the map, closer to Dumfries, Davis appears to have withdrawn his northern most pickets south of Powells Creek between March 6 and March 14 and suggested replacing them with a patrol force. By March 16, the patrol had been instituted. On the later map, you will also notice that most of the roads are listed as wood or forest roads, suggesting the area may still have been heavily wooded or recently timbered. Though the changes are slight, one gets an idea of the fluid nature of the lines. Describing the roads as wood or forest roads suggests to me roads of the very roughest nature, even in good weather.

Above is a final version of my picket map. I have incorporated unit designations along the picket line, based on documents described below. I have also corrected, with help from John Hennessy, the area in Caroline County that the federals termed Port Tobacco. The correct name is Portobago, the name of the plantation onsite. Period maps, most of them Union maps, consistently show Port Tobacco but designate the small bay or inlet as Tobago Bay. Today, a small development carries the Portobago name.

One can see the distance between the depots at Aquia and Belle Plain and Dumfries. The combination of poor roads and distance led Pleasonton to suggest on February 25 that Davis draw his supplies from Dumfries. On one hand, a quick look at the maps proves Pleasonton’s point. However, shipping supplies up the shallow creeks to Dumfries proved labor intensive as everything had to be unloaded from the large, deeper draft vessels and onto a series of shallower draft vessels, some of which had to be poled up the creeks to the town. Nothing proved easy.

The Federals employed a form, termed a Journal, to be completed by cavalry commanders on a daily basis. I have located just a few dozen of these forms, with most linked to the late winter and early spring of 1863 and others to the same period of 1864. In other words, periods when the army was in winter camp. The sparsity of the forms suggests most have either been lost, or cavalry commanders completed them on a sporadic basis. The earliest ones I have found are dated March 16, which coincides with the picket maps here and happens to be the day before the fight at Kelly’s Ford. As I consider the information noted on the forms, especially as pertains to the condition of the horses, one has to wonder just how much the Federals could have reasonably hoped to achieve on March 17.

The forms note the length of the unit’s picket line, the number of men on picket, the number of men on patrol, the number of men in camp, the condition of the animals, including the number that had died since the previous report, and lastly, significant events that had occurred since the previous report.

I have located completed forms for Pleasonton’s 1st Division, Gregg’s 2nd Division, and Buford’s Reserve Brigade for March 16. Colonel Davis’s picket line (diagramed on the maps above) is described as follows: “Length of vidette line seven miles, from Chopawamsic Creek Church to Dumfries. The vidette line and the Telegraph Road from Dumfries to Occoquan is habitually patrolled. Strength of detail … 470 men of the 8th Ill. Cav, [under] Lt. Col. [David] Clendenin.” I believe this works out to 67 men per mile, if all 470 men were on the picket line. In reality, one third, or 160 men, would have been on picket, about 22 men per mile, with the other men on patrol or at rest.

Patrolling the line meant a round trip of more than 14 miles as the men checked both the forward pickets/videttes and the reserve posts. Patrolling the telegraph line to Occoquan probably meant a round trip of 20 miles or more each time. And, as a trooper in the 8th Illinois described on March 15, while on the route, “for three good miles it was up to our horses’ bellies in frozen mud.”

Regarding the 2nd Brigade, the journal reads: “The line picketed by this brigade is ten miles in length, detail for picket 375 officers and men [between 12 and 37 men per mile]. Major [Peter] Keenan, 8th PA Cav in command. Patrols all approach from Brentsville, Warrenton, and the fords of the Rappahannock, also the Telegraph Road from Aquia Creek to Dumfries.

As to patrols, the journalist for the 1st Brigade explains, “Lt. [Bryant] Beach with 25 men scouted the Warrenton Road, and Capt. White [John Waite, I believe] with 15 men [scouted] the Brentsville Road. Patrols defensive from main reserve every three hours, from Dumfries to Occoquan every six hours. Last patrol from Dumfries missing.” We do not know the length of these patrols.

The journalist described the 2nd Brigade patrols as, “all defensive. Report all quiet, one at [daylight] 10 men and one at night 20 men. No communication with patrols from Occoquan. Object of patrols to protect telegraph.”

As to the number of men in camp and the condition of the animals for the 1st Brigade, “For duty 62 officers and 900 men. Condition of animals poor, except 8th Illinois Cavalry.”

For the 2nd Brigade, the “6th NY counted 21 officer and 403 men, the 17th PA counted 27 officers and 400 men, and the 8th PA had no troopers in camp for instant duty for want of horses and equipment. Horses in general good condition.

Regarding events, “Lt. Col. Clendenin reports that a patrol of a corporal and six men from Dumfries to Occoquan is missing. Lt. Col. Clendenin’s written orders were to send a platoon on the road. Look here for more on this incident.

The journalist said of the 2nd Brigade, “There is a space of 2.5 miles between Gen’l Averell’s right and the left of the picket line of this brigade open to the enemy. Country in front of the line scouted on the 14th by a party from the 8th PA now on picket and no enemy found. Bushwhackers still hold the woods. Major Keenan reports tonight that connection has been renewed.”

I believe the comments describing all patrols as defensive are instructive. By keeping troops, such as the Iron Scouts, on the Northern side of the Rappahannock, Stuart and Hampton not only kept Stoneman’s cavalrymen on their heels but prevented them from making incursions across the river themselves, thus allowing the Southern cavalry to rest, while exhausting Stoneman’s men and horses.

Rather than cite the entire report for the 3rd Division, I will note that Gregg’s division held the other end of the line in King George County. Lt. Col. [Calvin] Douty, 1st Maine, with 739 officers and men secured a line 12 miles long. Gregg counted 601 unserviceable horses in the division. The journalist’s description of Gregg’s line as 12 miles long is only partly correct. Twelve miles refers only to the main line between Corbin’s Neck and Port Conway, but the men also secured the road we know today as Rt. 301, running between Port Conway, on the Rappahannock River, and the Potomac River, a distance of another 15 miles or so.

John Buford’s Reserve Brigade held a line 7.5 miles long, between the infantry pickets near Fredericksburg and Corbin’s Neck with 300 men of the 6th US Cavalry. The officer who completed the form noted, “800 men…left camp at 8a.m. to report for duty to Gen’l [William] Averell for reconnaissance. Object not known. Result not known.” These were the men from the 1st and 5th U.S. who participated in the Kelly’s Ford fight, and I find the level of secrecy interesting. The Brigade counted 983 men and 23 officers and the officer completing the journal described the condition of animals as “poor.”

The maps and journals are both interesting and instructive, as they help us to understand the scale of the task placed upon the cavalry and the resulting toll on the horses. In his journal report for March 21, Gregg counted 619 diseased or unserviceable horses in the division and cited 13 as having died since his previous report. Seven days later he counted 645 horses unserviceable with 11 having died since his last report. The numbers improved slightly on the March 30 report, with 624 horses reported unserviceable but 15 having died. On April 1, Gregg listed 673 horses unserviceable and 22 having died.

To date, I have found few such reports for the 2nd Division, but one dated May 21 is worth noting. Led by William Averell on the Stoneman Raid, the division had covered fewer miles than the other commands and had been back for several weeks. Alfred Duffie, who replaced Averell, reported 1005 horses for duty and 853 horses unserviceable on May 21. He also described their condition as “very poor,” [Duffie’s emphasis].” The Gettysburg Campaign began just two weeks later.

Sources:

Documents in the National Archives

Thomas Benton Kelly Letters

The Official Records

Rod Andrew, Wade Hampton, Confederate Warrior to Southern Redeemer

Robert Driver, 5th Virginia Cavalry

Edward Longacre, Lee’s Cavalrymen

Adele Mitchell, The Letters of General J.E.B. Stuart

Robert O’Neill, Chasing Jeb Stuart and John Mosby

I can only speak for myself, but you are nowhere near my limit of tolerance for these incredible deep dives into the archives. And I really love a good map.

LikeLike

Thank you, Larry. Julie Krick makes the map process very easy.

LikeLike