Several years ago, I examined several of the challenges confronting Brig. Gen. Montgomery Meigs, Col. Rufus Ingalls, and their subordinates in the Quartermaster Department, as they struggled to keep the men and animals of the Army of the Potomac supplied during the winter of 1862-1863. You can find those posts here and here.

I want to revisit the winter, specifically December, and the need for and acquisition of hay for the Army of the Potomac’s horses. Though sharp-eyed readers will recognize that I am reusing some documents here from those earlier posts, I want to look at the problems impacting the supply of hay from another angle – what we term today the supply chain.

As Colonel Ingalls later explained, he began preparing for the army’s movement back into Virginia in late October 1862. Doing so entailed closing supply depots in Maryland and [West] Virginia and opening or re-opening depots in Virginia. After loading enough materiel onto wagons to supply the army for several days, Ingalls looked to establish the first new depots along the Manassas Gap Railroad, near the towns of Salem (present day Marshall) and Rectortown. The railroad, once back in service, allowed easy delivery from the large depots in Washington and Alexandria. On November 7, and with the army now along the railroad, President Lincoln relieved army commander George McClellan and promoted Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside to replace him.

As Burnside’s winter campaign developed and the army moved farther south toward Fredericksburg and the Rappahannock River, Ingalls continued to open and close depots, as he sought to keep the army supplied. With the season progressing deeper into winter, the army moved away from the security provided by access to a railroad, as no lines ran between Washington and the Fredericksburg area. The Potomac River and several tributaries became the main avenue of supply. Each move the army and Ingalls made impacted the supply chain.

On November 1, the army counted 37,897 horses and mules. On January 26, 1863, when Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker relieved Burnside, the army, now well into winter, counted 63,193 horses and mules, an increase of nearly 67%. Horses received a mixed daily ration of between 24 and 26 pounds of hay and grain. (In November 1863, General George Meade established the ration of 10 pounds of hay and 14 pounds of grain for horses. Per Meade’s order, mules received 22 pounds per day, the difference being only 11 pounds of grain.) Using only the lower figure of 24 pounds, the army’s 63,193 animals (as counted on January 26) consumed one and half million pounds or 758 tons of hay and grain per day. This included 632,000 pounds or 316 tons of hay. These figures may have been higher during the worst part of the winter of 1862-62, as all of the animals worked harder carrying or pulling their burdens along or through roads turned into quagmires and their rations may have been increased to help maintain their strength.

Though estimates tend to vary between sources, an army wagon carried about one ton on good firm roads. Based upon documents from the time period, 236 pounds seems a good average for a bale of hay. Thus, a wagon might carry eight bales, but other evidence suggests that the overall size and bulk of a bale would have limited a wagon to fewer than eight bales. The condition of the roads would have limited the amount each wagon carried even more. Based upon a smaller sample of information, bags of corn and oats weighed 113 pounds on average. The difference in weight and bulk between a bale of hay and a bag of grain seems to have been important, if for no other reason than the ability of a man to carry each item in the loading and unloading process,

Train cars carried about nine tons on average, but the bulk of the item made a difference here as well. Cars carrying hay carried on average just under four tons per car, while cars transporting bagged corn or oats carried an average of 12 tons per car. Hay would also have been combustible, and in the era of wood powered engines and sparks flying back from the funnel along the length of the train, fire became another concern.

Shipping varied drastically in terms of size and type, and I do not have enough specific information to hazard any kind of an estimate as to average capacity. The army chartered privately owned civilian vessels. Chartering steam powered vessels and tugs made deliveries more reliable than relying upon wind power. In December 1862, a correspondent estimated that the army’s need for hay – just hay – would “keep in constant employment a fleet of 200 schooners of 150 tons each.” But where did the hay come from? Put another way, what did the supply chain look like.

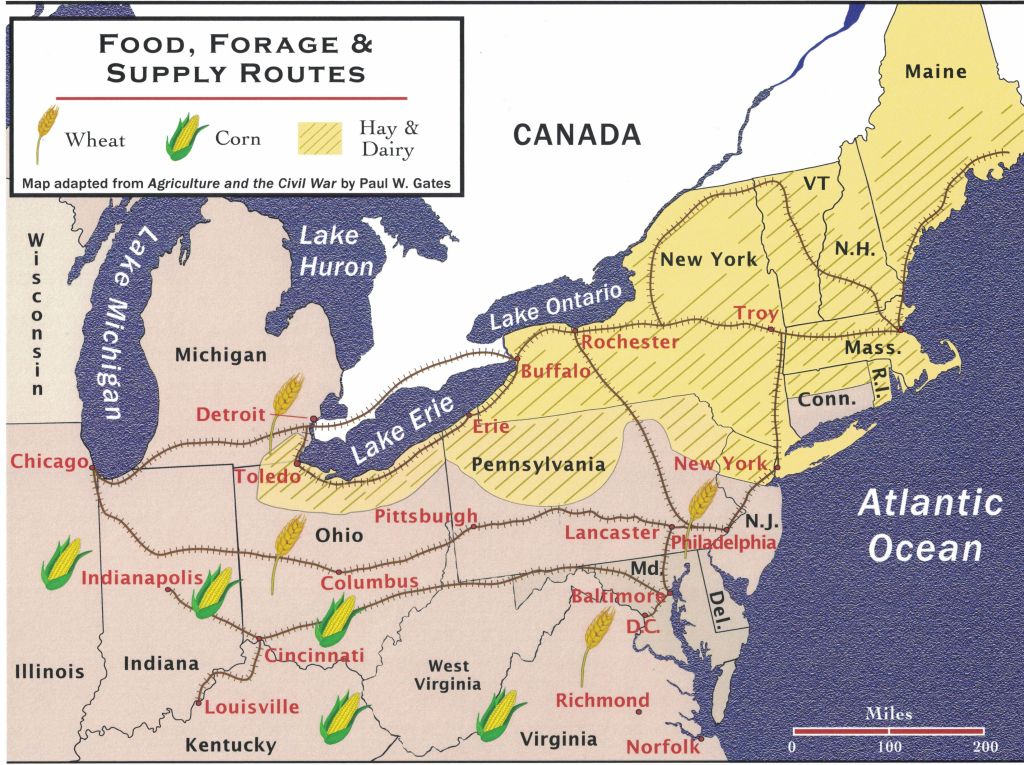

Julie colorized and narrowed the scope of the map to the northern half of the eastern United States. She also eliminated information not pertinent to my focus on horses and, in particular, hay or forage. You will quickly note that the northeastern states produced the majority of the country’s hay crop. I chose not to clutter the map with every railroad through the region. Suffice it to say, except for the northwestern corner of Pennsylvania, an abundance of railroads covered the area.

The army established two main hay depots along rail lines and waterways, at Philadelphia and Baltimore, with a third depot at Alexandria, Virginia. Quartermasters commanding depots throughout the region and Northern Virginia contacted either Capt. William Stoddard at Alexandria or the commander of the Baltimore depot when they needed a resupply of hay.

I suspect that trains provided the primary means of transport from the farm regions to the three primary hay depots, but no trains ran between Washington and Alexandria to the Falmouth/Fredericksburg area, leaving the army to rely upon wagons and shipping to make the last leg of the trip to Aquia/Belle Plain. A short military railroad linked Aquia to Falmouth. Colonel Ingalls, along with engineers and railroad officials, expanded that line in early December with the addition of a siding known eventually as Stoneman’s Switch or Stoneman’s Station.

The success of our supply chain today depends on our ability to anticipate what we need and when we need it so that we receive just what we need exactly when and where we need it. Thus, a long line of container ships and other vessels are in constant motion delivering products to our ports. Timed to arrive just as needed, these products are then moved inland by trains and trucks. If too many perishable goods are delivered too quickly or in larger quantity than necessary, some will be lost to wastage. Too little and we complain about empty shelves. Success relies upon a delicate balance of many moving parts, most of which are still impacted by bad weather, labor disagreements and more. Now imagine managing such a system without modern technology and communications.

At its core, the supply chain during the Civil War differed but little. Wagons and mules replaced trucks, the telegraph replaced e-mail and phones, and hundreds of clerks replaced computers. And none of the men involved had our satellites to help them to predict the weather. Recall recent photos of containerships stacked up outside our ports a couple of years ago. Residents and soldiers near the waterways between Baltimore, Washington, Aquia, and Belle Plain would have watched a steady stream of steamships and tugs pushing or pulling barges heavily laden with hay and other supplies. But over-estimate your needs, especially during the humid summer months, and the hay might turn moldy sitting on ships waiting along the waterways. Send too little or allow ice to close the rivers or mud to shut down the roads and horses might starve. Unfed horses meant the cavalry could not function and food and other materiel could not be delivered to the farthest reaches of the army. The same delicate balance existed during the Civil War as exists today.

When Colonel Ingalls ordered forage, he had to anticipate (a nice word for guess) just how much hay he would need for a certain period of time. He sent his orders to Captain Stoddard in Alexandria. Stoddard filled the orders and then ordered more hay from Baltimore to re-stock his depot. The officer at Baltimore then ordered more hay from Philadelphia and so on. The three depot commanders supplied materiel to depots and army detachments along the entire east coast and the Gulf of Mexico. During the winter of 1862-1863, the delicate balance crashed, largely due to water routes closed at times by ice, roads made impassable by rain, snow, and mud, and, whether real or perceived, the failure of key men to order hay in a timely manner and in appropriate quantity. Colonel Ingalls only had to anticipate the needs of the Army of the Potomac. Captain Stoddard filled orders for and had to anticipate the needs of the Army of the Potomac, as well as dozens of other depots or detachments of men and animals. The record suggests that in December 1862, when the system first crashed, Ingalls laid the onus on Stoddard.

As the Army of the Potomac continued moving south toward Fredericksburg, Ingalls visited the old supply bases at Aquia and Belle Plain on November 16 and found the facilities “a mass of ruins…” He ordered temporary wharves constructed, using “barges and trestle work,” and had them ready when the army arrived. In time, the army rebuilt a massive facility at Aquia, a second large landing at Belle Plain, as well as a third wharf at Hope Landing. In his report written in March 1864, Ingalls said “the depot at Aquia was made as spacious and commodious as any one we have ever had,” but he does not say when the facility reached peak capacity. In January 1863, General Meigs told a senator that the wharf, then 1,000 feet long, was “still insufficient for its purpose.” He also reported, “Over one hundred vessels are constantly in that harbor.”

Recreating an accurate timeline is difficult, but Capt. Colin Ferguson, another quartermaster at the Alexandria Depot reported shipping “to Aquia Creek and Belle Plain 125,000 feet of wharf timber and 60,000 feet of planks” on November 17. Recognizing that Ferguson shipped this lumber just one day after Ingalls examined Aquia and Belle Plain suggests the scope and scale of the depots in Alexandria and Washington, as well as the importance of getting the facilities back up and running.

Ingalls ordered another “100,000 feet of assorted lumber in addition to outstanding orders,” on December 1, and Meigs authorized an additional one million board feet of timber and plank for the wharf and railroad two weeks later. On June 1, just two weeks before the army abandoned the facility to the enemy for a second time, the army ordered materiel to extend one wharf again. I confess to not having copied every order for lumber I have seen during this period, but I think we get a sense of the size of the Aquia depot. While the orders here are rather specific, taken in total, much of the lumber ordered went into constructing offices, warehouses, and other buildings of one kind or another.

Having established a little background, let me return to a quote from Colonel Ingalls that I used in one of the previous accounts. On December 21, he complained to Captain Stoddard, “The whole army still complains of want of forage. For God’s sake, see that it comes quickly and have [the forage] in boats and on the river. See to it in person.” All of these years later, one still senses the developing crisis Ingalls felt and tried to convey to Stoddard.

Please note that Colonel Ingalls was based at army headquarters near Falmouth, where he received orders from the army. He then communicated the requests by telegraph to his subordinates at the supply bases at Aquia and Belle Plain and quartermasters in Washington and Alexandria. Stoddard was tasked with ordering hay and grain for and distributing the same to the many depots still operating around the capital.

Probably just before or immediately after haranguing Stoddard, Ingalls sent a similar message to Col. Daniel Rucker, commanding the depot in Washington, warning him “supplies of forage etc., are becoming short at Aquia and Belle Plain. We must have them and always beyond doubt or chance.” Ingalls also asked Rucker to send 1,000 mules and 200 horses “as early as possible.”

His emphasis on mules hints at the deterioration of the roads due to rain, snow, and the freeze and thaw cycle, as well as the difficulty of pulling loaded wagons through those quagmires. Seeking solutions, Ingalls sought to increase the number of animals pulling the wagons from four to six and he considered replacing wagon trains with pack trains.

Puzzled by the tone of Ingalls’s telegram and aware of what he had shipped in recent days, Stoddard queried his forage superintendent at Aquia as to the amount of forage then on site. Then, with the superintendent’s response in hand, Stoddard told Ingalls, “There are 17 vessels now at Aquia and Belle Plain loaded with forage. Most of these vessels arrived yesterday and the day before and none of them unloaded. I will make every effort to have the necessary ice boats on hand.” Stoddard’s message points to two of the important factors then impacting the supply chain, ice on the Potomac River, Aquia Creek and other shallow streams in the area, and the availability of laborers to unload vessels in a timely manner and then load the wagons that would carry the forage to the front lines. I addressed the question of ice closing the waterways in one of the earlier posts cited above and, while I have not addressed labor concerns during the winter of 62-63 in any detail, I did speak to the topic during the Gettysburg Campaign here and here.

Recall again the supply chain problems in the immediate wake of the pandemic of 2020-21, when, just as life seemed ready to resume some sense of normalcy, labor concerns at port facilities on the west coast left us, again, with empty store shelves at home and images of heavily-ladened containerships anchored outside the ports waiting to be unloaded. Hungry soldiers and frustrated quartermasters probably saw similar scenes all along the Potomac River and the smaller tributaries near the army in late December.

As Ingalls telegraphed Stoddard on December 21, Colonel Rucker opined to General Meigs, “it will require at least four boats to keep the river open if cold weather should be at all severe. Two large-sized boats of great power to run between here [Washington, D.C.] and Belle Plain via Aquia Creek, one light draught boat for service in and about Aquia Creek, and one light draught boat for Belle Plain.” As the boats had to be located and chartered, Rucker asked Meigs to “give the necessary orders to procure them with the least possible delay.” With hay being delivered from New England, New York and elsewhere, every link in the supply chain had to be operating at peak efficiency for the men and animals with the army to be fed and to stay healthy.

On December 23, Ingalls complained again to Stoddard; “There is still a great want of forage at our depots… Let me comprehend why at this late day we have not an abundance of forage. The animals perish and my department falls into disrepute. Do not be afraid of sending too much or too soon. Send it forthwith … I cannot much longer withstand these constant complaints. Please tell me what I may expect.”

We might easily understand any confusion Stoddard felt upon reading the message. Had the 17 vessels loaded with hay and sitting unloaded in the river two days earlier already been unloaded and the supply exhausted?

Unfortunately, many of the surviving telegrams are undated and thus rather useless to anyone trying to recreate the historical record. Of the dated messages, many do not reflect the time sent or received, further degrading attempts at accuracy. That said, I believe Stoddard responded by telling Ingalls, “I don’t know why it is that you are short of forage. There has been more forage at Aquia and Belle Plain for [the last 4 or 5 days] than could be unloaded. It has been accumulating daily. Yesterday there was over 80,000 bushels of grain at the two places and 500 tons of hay. I will increase the above to any amount you desire.”

Ingalls replied, “I have referred your dispatch to [my subordinates] with orders to answer it. I have simply to remark that the latter informed me today he had hardly any forage and officers who went there today state [they were not supplied] … I want 20 days’ supply at once for 40,000 animals (Remember the estimate of 63,193 animals is through the end of January). I want the hay as well as the grain. Let me have it forthwith and I wish you to see that it is divided properly between Aquia and Belle Plain.” Though he is the quartermaster general for the Army of the Potomac, Ingalls is essentially a middleman here, receiving messages and complaints from his subordinates at Aquia and Belle Plain, as well as fielding requests and complaints at headquarters from unit commanders and passing them all along to Stoddard.

Using the figure of 24 pounds for the daily ration per animal, the daily supply for 40,000 animals weighed 940,000 pounds or 480 tons. A 20-day supply would have weighed 9,600 tons. Estimating the number of ships and barges needed to move such volume is impossible. However, considering that an army wagon carried about one ton on good roads, one easily sees the scope of the effort needed to move 9,600 tons from depot to wharf at Alexandria and then from wharf to depot at Aquia and Belle Plain and then out to the widely scattered smaller components of the army.

A message from the commander at the Baltimore depot to Rucker on December 23 expands our understanding of the supply chain. “[I forwarded today] by rail 741 bales hay and 360 bales straw. By schooner 450 bales hay. Two schooners left yesterday with 222 tons coal. Five schooners now loading will be off tomorrow.” The mention of coal gives us a sense of all the other materiel being shipped to the army and the need to keep the river open, but the officer also leaves us uncertain as to what he was loading on the five schooners he mentions, forage or coal.

On Christmas Eve, Ingalls learned from a subordinate at Belle Plain, “…on the 20th we got out of forage entirely. None was at the wharf or at the mouth of the creek. I sent to Aquia and obtained all I could which was 2 schooner loads. All the forage that has arrived at that place in the last 4 days is 1,794,022 pounds of oats. 1,057,268 pounds of hay. One schooner and part of another is all we now have on hand. We have received but a little more than a half days’ supply of forage in the last 4 days.” Forwarding the information to Stoddard, Ingalls told him, “I have to repeat again the order that you will place at Aquia and Belle Plain without delay a supply of forage for 20 days.”

On Christmas, Ingalls sent a lengthy report to General Meigs, expressing his view of the situation going back to September and stressing the need for ships of light draft to bring materiel into the shallow harbors at Aquia and Belle Plain.

“… For the past ten days this army has suffered much for want of forage, mainly because the depots at Washington and Alexandria have failed as usual [his emphasis throughout] to put their establishments on a scale commensurate with our actual wants.

“In September … I expressed … a fear that unless energetic and immediate measures were adopted, winter would find us deficient in supply. It seemed as if the magnitude of five thousand tons of hay, the amount I ordered to be placed in depot at Alexandria, alarmed the officers in charge. It was in September that the forage should have been provided. We had the experience of the preceding year and still did not benefit by it. The Treasury is not depleted so much by the charter of a few light draft boats, as it is by delay and inefficient arrangements in the purchase of supplies. Oats were only 65 cents then, now they are 89 cents per bushel.” The laws of supply and demand have not changed.

Continuing, Ingalls explained, “The first ten days on this line exhausted the supply of forage on hand; since then, we have been at the mercy of contractors with a constantly increasing price. We want here now, at least a twenty days’ supply… to answer for any severe weather or closing up the Potomac… To land this forage and other supplies requires great system, and very many facilities. [You] are aware that the water at Aquia is shallow & the channel narrow, at Belle Plain it is still more so, the bottom at the latter place being a very deep soft mud, through which barges cannot be poled [Note the additional labor involved]. In times of low water and ice, nothing can be done with barges. It is only with the aid of light draft steamers that the work can be done. I wish no expensive vessels, but cheap stern and side wheel steamers, sheathed for breaking ice when necessary. We should have four at each place for local use. This is exclusive of vessels used for other purposes. If the two applied for be sent, and those in service put in repair, there will be enough. It is probable that several heavy tugs and steamers now under pay might be discharged, and a considerable expense saved. We must have ice boats which can be sure to keep this river open all winter, else this army must go elsewhere very soon. This is a very important consideration.

“We have men enough to do all necessary work at the depots. They are employed unloading transports, making landings, corduroying roads, [etc.]. I beg you to order the boats, and rest assured I will ask for no unnecessary articles, nor engender a cent’s unnecessary expense.”

I have not been able to document whether or not ice was present on the creeks and rivers or, if present, the degree to which it hampered the delivery of materiel. Ship logs, especially from Navy ships, would probably be the best means of determining if ice did or did not hamper supply ships. Until then, let me say that temperatures recorded in Georgetown for the period of December 21 to 27 do not support the presence of ice to any meaningful degree. However, low temperatures for December 18 to 20 were 13, 22, and 29. By December 21, the low was 36 and rose over the next several days. Temperatures at Aquia and Belle Plain may have been a few degrees warmer. So, I believe ice may have been present when Ingalls complained on December 21, but the threat probably diminished over the next several days.

On December 27, Ingalls told Stoddard, “You do very well now in the shipment of grain, but you do not send enough hay. You must send 500 or 600 tons daily, if possible, for some time to come. We require the hay in this weather.” To which Stoddard replied, [My superintendent] reported to me yesterday that there was at Belle Plain and Aquia Creek 113,093 bushels of oats, 30,850 bushels of corn and 4075 bales of hay (about 481 tons). In addition to the above I shipped from here 15,240 bushels of oats, 7500 bushels of corn and 2046 bales of hay (240 tons).”

The same day, Ingalls told Colonel Rucker to “please send mules as rapidly as possible so that our teams may be strengthened to 6.” As mentioned previously, his desire to increase the number of animals pulling wagons and artillery suggests the deterioration of the roads as winter progressed. Doing so also increased the number of animals to be fed and put further strain on the system.

By January 14, 1863, the situation had improved, as Ingalls told Meigs, “This command is well off for forage and all our teams are in excellent condition.” Concern raised by ice on the river and creeks, the need for more shipping, or tons more hay is soon replaced by calls for more horses.

Sources:

Documents at the National Archives

The Official Records

The New York Times

Robert K. Krick, Civil War Weather in Virginia

I had no idea of the amounts involved, and this is just for the horses and mules. That the system really worked so well is equally impressive.

LikeLike

In my opinion, Larry, most logistical studies are written as basic primers from the 50,000-foot level. I believe that we can only really appreciate the challenges by looking from the ground level, but the numbers could or would be so overwhelming as to lead most readers to book any such study aside. But the information is available.

LikeLike

Different war, same topic: “Beans, Bullets, and Black Oil – The Story of Fleet Logistics Afloat in the Pacific During World War II”.

LikeLike

It is difficult to comprehend the scale of the supply problems the Union Army faced in southern Stafford County during the winter of 1862-63 but you have done it Bob with your extensively researched article on the subject. I assume that Lee’s supply problems were the reason he sent Longstreet’s Corps south to Suffolk county that winter.

LikeLike

It is difficult to comprehend the scale of the supply problems the Union Army faced during the winter of 1862-63 while they were camped in southern Stafford County but you have done it Bob with you article, extensively researched and well documented as always. I assume that Lee’s own supply problems were the reason he sent Longstreet’s Corps south to Suffolk County that winter. Thanks again.

LikeLike

It is difficult to comprehend the scale of the supply problems the Union Army faced during the winter of 1862-63 while they were camped in southern Stafford County but you have done it Bob with you article, extensively researched and well documented as always. I assume that Lee’s own supply problems were the reason he sent Longstreet’s Corps south to Suffolk County that winter. Thanks again.

LikeLike

Thank you, Bob. While concern for feeding his men and animals was not Lee’s only reason for sending Longstreet to Suffolk, I believe it was certainly one reason, as he had also been dispersing his cavalry to ease the logistical burden and to save his horses, and he would at about the same time reduce his soldier’s daily ration.

LikeLike