In March of this year, I wrote an article regarding the Spencer carbine postwar. I had been intrigued as to why the army ordered several cavalry regiments, including those of the Michigan Brigade, to turn in their Spencers and later replaced them with single-shot Joslyn carbines. Searching for a definitive answer as to why the army had done so, I began examining the voluminous Ordnance Department records in the National Archives. The task has proved interesting. While many useful documents have been found related to the Spencer, as well as to models manufactured by other companies, I have not found the ‘smoking gun’ I had hoped to. However, based upon information I have found, I feel confident in drawing some early conclusions.

When the Michigan Brigade turned in their Spencers, a Southern army remained in the field in Texas, the threat of an invasion across the Rio Grande by French forces in Mexico loomed, conflicts with Native Americans began escalating and Reconstruction laws needed enforcing. At the same time, the army began disbanding the volunteers and cutting back on wartime expenditures. Stating the question another way, I asked if the army tried to do too much with too little too quickly? I believe several factors contributed to the army’s decision.

The Spencer was both heavier and more expensive than other carbines, and, with more working parts than other weapons, more easily damaged.

Robustness and Reliability

In January 1863, shortly before the men of the 5th Michigan Cavalry received their Spencer Rifles, the colonel issued the following order:

“…Before issuing…the splendid rifles and equipment that the Government will place in their charge, the commanding officer hereby cautions them that they are a most expensive weapon and must receive the finest attention and care. No needless cocking, nor forcing back and forth the guard will be allowed and on no account must a screw or band be started. A weapon injured through neglect or carelessness will be charged… and deducted from the man’s pay. Should a gun be injured or clogged it will be taken to a field officer for inspection and no attempt made to repair it until he has been consulted…”

I will confess that as a young boy I loved working the lever on my first toy lever-action, cocking, firing and re-cocking the weapon in the face of an imaginary enemy. I did the same when I purchased my first real lever-action as an adult. I feel certain the young Michiganders were just as enamored with the new rifles and the mechanism that set them apart from other weapons as I had been with mine. I can only imagine what the company camps would have looked and sounded like but for the order.

The colonel directed that any damaged weapons would first be taken to a field-grade officer for inspection. He does not mention regimental armorers or men within the ranks who had been trained to repair weapons in the field. Without such men, damaged or unserviceable weapons went back to an armory or arsenal for repairs and the troopers may or may not have received a replacement. The earliest mention I have of regimental armorers in a document is from late-September 1863. These men received an additional 40 cents per day, but issues over the pay arose and the extent to which the position truly took hold is unknown. Nor did everyone see a need for such men.

In late-November 1864, George Custer sent a letter to the Adjutant General requesting “…a competent armorer may be detailed and directed to report to these HQ for the purpose of instructing men to be selected from each regiment of the division, in the use of tools and parts of arms necessary to effect slight repairs in arms needing them to render them effective. But one regiment of this division had an armorer and that one is absent. I am confident that great saving to the government and much benefit to the command must result from a favorable consideration of the application.”

Custer had that day sent 272 carbines, including 109 Spencers, “most of which need slight repairs to put them in order,” back to the Ordnance Department. As he concluded, “Many similar [lots] accumulate during campaigns, becoming unserviceable from some slight cause. They are carried with the command upon pack animals, and many are lost or damaged before they can be turned in… while, as now, men are with the command, unarmed for want of these articles.”

Though Custer’s request appears sensible, not every officer agreed. Just two weeks earlier, an officer had inspected the arms carried by the 10th New York Cavalry. The regiment carried four different carbines but no Spencers. In his comments, the officer noted, “The employment of a regimental armorer in the field is impracticable, as all arms requiring repair are turned in for that purpose to the Chief Ordnance Officer.”

In December 1867, Lt. William Parnell (read my account of Parnell’s career here), then stationed in Oregon, addressed his own concerns with the Spencer to the Ordnance Department. Parnell deemed the Spencer an “excellent” weapon, but he also noted some liabilities.

“It …requires to be handled with more care …and consequently requires a new system of tactics, or maneuvers. I find from experience that, at the command “Order Arms,” the butt of the carbine is very liable to be brought down on a stone, or rock, and even with the greatest precaution, the striking of [the] magazine [nut] on the stone is very liable to snap the magazine lock-catch, thus leaving it almost useless, until repaired, which in these frontier posts, is almost impossible.

“In wet weather, when at ‘Order Arms’ … dirt gets into the magazine. Sometimes clots of mud will get in, and not only render it difficult to get out, but is very liable to interfere materially with the interior mechanism of the carbine. Even with the greatest care this will occur…in muddy weather.

“In wet weather, I also think that at Parades, Inspections, and Guard Mounting, the opening of the lever should be dispensed with, and thus avoid the [works] getting wet. At many posts (this for instance) it is difficult to obtain any oil whatever, so that the works of the lever requires to be kept perfectly free from dampness or rain…”

Such concerns aside, Peter Schiffers in his study, Civil War Carbines, Myth vs. Realty, gives the Spencer a ten out of ten for, what he terms, robustness or the ruggedness of all the parts of the carbine.” Schiffers gave the Joslyn Carbine, the weapon the Michiganders received as a replacement, a four.

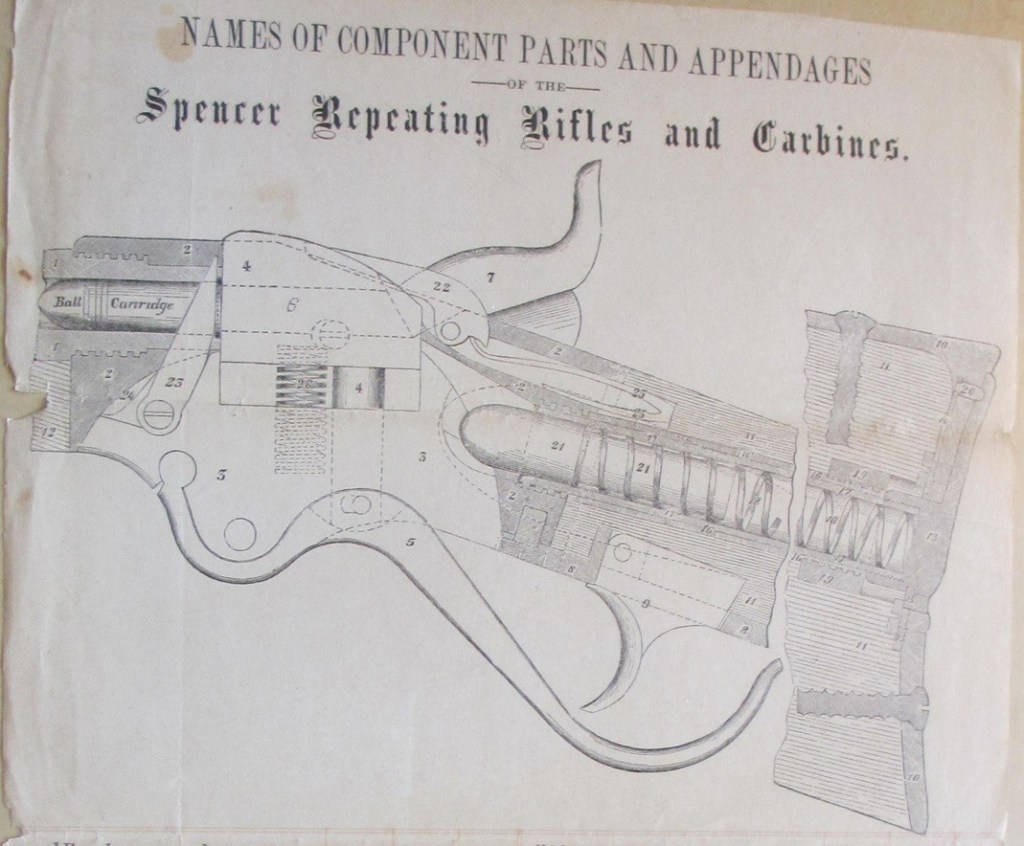

In his letter, Parnell refers to the weapon requiring “a new system of tactics, or maneuvers,” possibly, in part, to avoid the problems he describes. A trooper loaded the Spencer through the stock or butt plate, by unlatching a spring-loaded metal magazine tube. Removing the tube, the soldier then loaded his metallic cartridges and reinserted and locked the tube in place. The spring, now under tension, pushed forward a new round when the soldier worked the lever. If the tube could not be locked into place, the carbine became a single-shot weapon, with the trooper manually inserting each round.

There are other references to a new system of drill and tactics being created for regiments armed with the Spencer. In March 1863, just weeks after the men of the 5th Michigan received their Spencer Rifles, their lieutenant colonel reminded the governor, “we have a peculiar rifle, and our drill has been made different from any tactics to adapt it to the arm and make it useful.” A manual of arms for the rifle was published in 1864, though I do not know the extent to which the army adopted the work.

Many readers may not realize the disaffection felt by soldiers retained in service after the war or the extent to which these disaffected men rebelled against orders and authority. Soldiers often expressed their anger by refusing to follow orders, especially orders to drill. Further, potential conflicts along the border with Mexico or against Native Americans would, most likely, be mobile affairs, making dismounted drill, and the problems described by Lieutenant Parnell moot. During his time in Louisiana and Texas, Custer, for one, called for his men to drill twice per day, except Sundays, and ordered that all drills be mounted.

Still, long tenuous lines of supply, especially on the plains, would have made repairing and replacing damaged weapons difficult. Thus, issuing a simpler weapon, that is one with fewer working parts, probably made sense to the senior officers in Washington.

Weight

Likewise, mobile warfare across the vast expanses of the western plains, coupled with the difficulty of resupplying the men, emphasized the need to keep the horses healthy. Reducing the weight the animals carried proved critical. The 1860 Spencer weighed 9 pounds, 2 ounces, while the Joslyn weighed 6 pounds, 10 ounces. The difference may seem insignificant, but every pound counted. Peter Schiffers gave the Spencer a 0 out of 5 for weight, while giving the Joslyn a 3.5 out of 5.

In 1864, the army sought to standardize carbine cartridges. After considering both .44 and .50 calibre as a standard, it initially adopted the .44 before reversing itself and choosing the .50. Having settled upon a standard calibre, the army then chose the metallic Spencer cartridge. Then, in January 1865, the army directed Spencer to reduce the length of the carbine barrel from 22 inches to 20 inches. The changes reduced the weight of the weapon to 8 pounds, 5 ounces, though still nearly 2 pounds heavier than the Joslyn.

As the army sought to standardize the calibre of the many different weapons, it also began to standardize the ammunition. The metallic Spencer round held several advantages over other ammunition, including durability. More importantly, the rounds already contained a primer, eliminating the need for a separate primer/percussion system. And, by 1865, several other manufacturers, including Gallagher, Starr, and Warner, had adapted their models to use the Spencer cartridge.

Soaring Demand in 1865

Probably because the Spencer was more difficult to produce, the company often struggled to meet deadlines. Army demands for changes, including but not limited to the shorter barrel, further slowed production. By the spring of 1865, Burnside Firearms had converted its factory to produce Spencer carbines, but the change came too late as the war was already winding down. Still, as often happened, officers in the field found their own solutions.

In March 1865, as he prepared for his massive cavalry raid through the deep south, Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson sought to equip every one of his men with a Spencer. Unable to acquire the weapons in sufficient quantity to do so, Wilson determined which units would accompany him on the raid and which units would remain behind. The units slated to remain behind then exchanged their Spencers with the other regiments, either per orders or voluntarily. In response, Wilson acknowledged the “generosity, gallantry, and zeal” of the units remaining behind and promised to reward them with the best horses, “equipments and arms the country can furnish.” In other cases, regiments received the carbines based upon their reputation or their prowess on the drill field.

Still, demand soared, even as the war came to an end. On April 20, 1865, the commander of the Ordnance Department responded to another requisition from Wilson’s Ordnance officer, “asking for 4,600 Spencer Carbines to be sent to … Nashville for the 5th Cavalry Division.” The officer then confirmed that he had received a few days prior “requisitions from the same division for nearly 6,000 Spencer Carbines.” The weapons could not be provided.

In a June 26 letter to a Cleveland newspaper, a trooper in the 2nd Ohio Cavalry, then near Rolla, Missouri, told his readers, “Spencer carbines cannot be procured as the approval of the War Department is needed on the requisition.” Like the men in the Michigan Brigade, the Buckeyes were headed west and, as the trooper explained, “there was not time to” obtain the necessary authorization. Despite these shortages, however, the commander of the Ordnance Department had agreed, on June 6, to let honorably discharged soldiers purchase their weapons for specified prices, including Spencer carbines for ten dollars apiece.

I believe all the factors mentioned contributed to the army’s decision. Other possible reasons need more supporting documentation, and I may present them in a future post. But I want to conclude by coming back to the Michigan Brigade specifically.

On June 15, 1865, even as the army allowed discharged troopers to purchase their Spencers, a soldier in the 7th Michigan Cavalry, noted, “We get revolvers in place of the Spencer carbines that we had.” In other words, the Wolverines had turned in their Spencers prior to June 15.

The men had reached St. Louis prior to June 2 when they departed for Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The 6th Michigan then departed Fort Leavenworth for Julesburg, Colorado, about June 16.

On June 1, the officer commanding the St. Louis Arsenal filled out a routine monthly report, in which he enumerated all the weapons on hand at his arsenal by make and model. He counted 1,132 Spencers.

On June 17, the commander of the Ordnance Department instructed the same officer at the St. Louis Arsenal to send 2,000 Spencers to Memphis, Tennessee and another 1,000 to New Orleans. Two days later, the officer in St. Louis replied, noting that he had shipped “all the Spencer Carbines on hand – 2,350. Two-thirds to Memphis and balance to New Orleans.”

During the 18 days between June 1 and June 19, the officer had gained 1,220 Spencer carbines. The timing suggests to me that the additional carbines had been turned in by the Wolverines. But why ship the weapons to Memphis and New Orleans?

In 1864, France had invaded Mexico, overthrown the government and installed Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian as emperor. As the Civil War came to an end, the administration in Washington believed the French might seize the opportunity to invade Texas and reclaim Mexican territory lost years earlier. Thus, on May 17, Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant ordered Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan to New Orleans. Sheridan’s primary mission was two-fold: “restore Texas, and that part of Louisiana held by the enemy, to the Union,” and, more importantly, “Place a strong force on the Rio Grande.” As Grant emphasized, “To be clear on this last point, I think the Rio Grande should be strongly held, whether the forces in Texas surrender or not, and that no time should be lost in getting there.” Grant promised to send as many as 25,000 men, including two small cavalry divisions led by generals Wesley Merritt and George Custer.

Though I have not seen any documents expressly linking these events, I believe the administration saw a possible conflict with France along the Rio Grande as the most pressing of the several potential conflicts brewing in the spring of 1865. As a means of meeting or heading off the threat, the army sent Sheridan to command the troops and gave his cavalry the best weapons available on short notice. Put another way, a conflict with France superseded the threat posed by Native Americans. With stocks of Spencer carbines nearly exhausted, the Michigan Brigade provided a ready alternative. The brigade’s timely arrival in St. Louis, along the Mississippi River, proved fortuitous as the cavalry assigned to Sheridan was then gathering in Memphis and New Orleans. Following General Wilson’s earlier solution, the army, as my parents like to say, ‘robbed Peter to pay Paul.’

Sources:

Documents from the National Archives

Documents found on Fold 3

Austion Blair Papers, Burton Historical Collection

James Kidd Letters, Bentley Library, University of Michigan

Muscatine (Iowa) Evening Journal

The Official Records

Roy Marcot, Spencer Repeating Firearms

Peter Schiffers, Civil War Carbines, Myth vs. Reality

Philip Sheridan, Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan, Vol. 2

Emmet West, History and Reminiscences of the Second Wisconsin Cavalry Regiment

I can never visit Gettysburg without visiting The Horse Soldier and seeing if they have a Spencer on display. However, I’ve never asked a vital question – how much does the ammo cost?

LikeLike

I noticed you are coming to speak at Blenheim this month. I’m a nurse and a history nerd and I’m wondering if you would be ok having your presentation filmed and put on YouTube?

channel is Let’s Go Rachel and I do local (Va, Md, Pa) travel content.

LikeLike

Sure, no problem.

LikeLike