In January, I wrote a piece on the Army of the Potomac’s advance back into Virginia in mid-July 1863. I focused on George Custer, temporarily commanding the 3rd Cavalry Division, in the Loudoun Valley, and you can find the story here.

On July 22, Custer wrote a detailed message, telling Gen. Alfred Pleasonton of a prisoner his men had captured at Ashby’s Gap and passing along information gleaned from the man. I found the most basic part of the story especially intriguing, not for the information reportedly provided by the man, but rather where the soldier was from and where he was going.

As Custer explained, “I saw the prisoner’s pass to visit his mother, residing near Upperville, and remain two days…The prisoner belongs to the Fourth Texas…The man is very intelligent, rather elderly, and does not intend to re-enter the service. I will forward him to corps headquarters soon.” I suspect everyone sees the interesting point here; the soldier belongs to the 4th Texas Infantry and is going to see his mother in Upperville. If I could identify the man, I thought I could determine where his mother lived.

Custer found the man very loquacious, telling Pleasonton, “He says their pontoons are laid across the river at Front Royal. The army has been lying for several days in the vicinity of Bunker Hill. He saw several other corps there. His division passed a large body of cavalry camped in the woods between Millwood and Berryville but cannot tell who was in command. Hood’s division crossed at Falling Waters; marched to Millwood, via Bunker Hill, Smithfield, and Berryville. The prisoner states that the impression in the Southern army is they are going back to where they first started from, by way of Markham Station. He reports a loss of 17 general officers in the battles of Pennsylvania. Hood was shot through the arm.” Custer then concluded, “I consider the above statement perfectly reliable.” Reading Custer’s message, I did not consider trying to verify the information the soldier provided but rather to identify the soldier.

I immediately thought of two friends, one is the leading authority on the men of the Texas Brigade. The other has compiled a database of the young men who went to war from Upperville. Even though several hundred men from the brigade had been captured during the campaign, my friend soon provided me with two names, suggesting one to be a better candidate than the other. Looking at his information, I agreed and texted the information to my Upperville authority. We had a response within moments, though with several details still to clarify.

Along with my wife, the four of us spent the better part of a day sorting out several anomalies and seeking as much information on the man as we could find. I let my wife handle my genealogy questions, as I have no head for such things. That day I pitched in, and truth be told, I am sure I created more confusion than clarity, but by the end of the day, and with my head still spinning, we knew we had our man.

Dugald Cameron Fitzhugh enlisted in Company E, 4th Texas Infantry, on July 13, 1861, in Waco, Texas. Except for a hospital stay in Richmond during the summer of 1862, followed by a three-day furlough, Dugald Fitzhugh marched and fought with the regiment until captured by Custer’s Wolverines on July 21. He remained a prisoner at Point Lookout, Maryland, until exchanged in March 1864.

According to family records, Dugald came into the world about 5 a.m. on January 12, 1823, the second son of William Colville Fitzhugh and Matilda Whittaker Helm Fitzhugh, of Upperville, Virginia. They named another son, Champe Summerfield Fitzhugh, Champe (sometimes Champ), being a name from his mother’s family. Champe also served in the war, with the 6th Virginia Cavalry and later John Mosby’s 43rd Battalion. Some confusion set into our early search efforts as Champe/Champ also appears in Dugald’s records.

At the time of his death in 1847, their father owned at least 404 acres in Upperville, an estate believed to have been called The Grove originally, later Brook Meade, and now Lazy Lane. According to his will, William also “had claims to 9,000 acres of Texas lands.” As he explained, William “deemed it important for the interest of the family that some one or two of his sons should go to that country to secure said lands and make them available.” He appointed Dugald to go and left him 1,000 acres of the land in Texas as compensation for the duties assigned him. Thus, Dugald found himself in Texas in 1861.

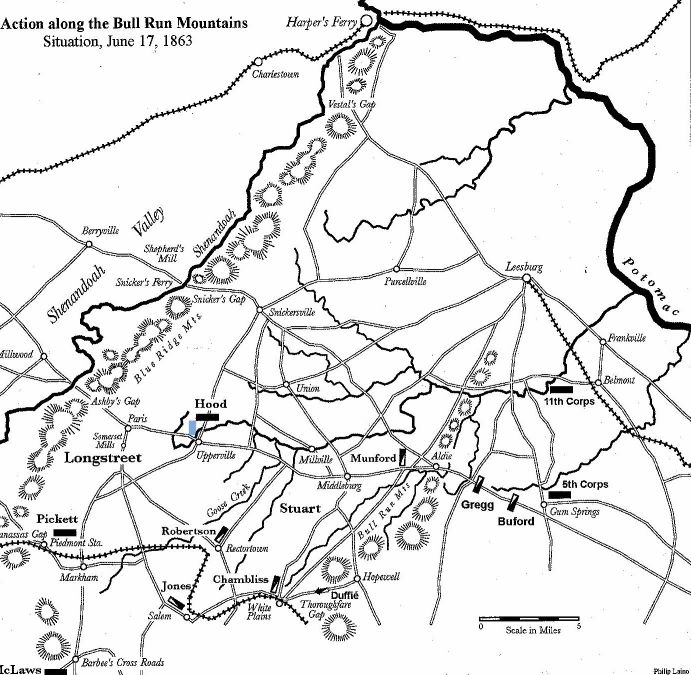

In June 1863, as the men of the Army of Northern Virginia marched north, Dugald passed the mid-point of his fortieth year. Still a private, he would have been considered an old man by his comrades, and on June 17, he must have felt every one of his years as he marched through nearly impenetrable dust in staggering heat. As author Douglas Haines describes the events of June 17, “Hood’s division marched to Upperville, and due to the extreme heat, not half the division was able to keep up with the colors. The residents of Upperville opened their doors to the weary Confederate soldiers and provided them with bread, milk, butter and water.”

The location of the Fitzhugh farm is marked in blue.

If Dugald remained in the ranks that day, he marched right past his family home. The men may have camped on the property and his family may have provided food and water to the exhausted men. On June 21, the last shots of the day-long battle of Upperville had been fired in the roads and fields around the farm. By then, however, Dugald and his fellow Texans were posted along the heights of the Blue Ridge around Snicker’s Gap.

On July 21, and with the Army of Northern Virginia again in the Shenandoah Valley, Dugald received the pass to visit his mother and siblings in Upperville. After wading across the Shenandoah River, he followed the Ashby’s Gap Turnpike up into the gap. Somewhere along his route, he encountered Union cavalry pickets from the Michigan Brigade. Taken into custody, he soon had an interview with George Custer and then began another journey, this time to a Union prison camp. Exchanged in March 1864, Dugald’s service appears to have ceased. All these years later, can we truly appreciate the toll the war had taken on him, a toll that led Custer to describe him as “elderly” at forty years of age.

My thanks to my wife, Teresa, Rick Eiserman, and Claiborne Stokes.

Sources:

Ancestry.com

Virginia Chancery Claims Files, Library of Virginia

WikeTree.com

The Official Records

Douglas Haines, “The Advance of Longstreet’s First Corps to Gettysburg,” Gettysburg Magazine, 2008, to include Philip Laino map.

Wynne Saffer, compiler, Loudoun County, Virginia 1860 Land Tax Map, Jonah Tavenner’s District.

Bob, excellent detective work, and I am glad I was present when some of the sleuthing was done at the Sacred Trust seminar. I love it when authors/researchers get to the nitty gritty rather than spout the same old stories. By the way, Doug Haines was a wonderful gentleman as well as a Butternut and Blue customer until he succumbed to cancer about ten years ago.

LikeLike

As far as years go, he’s positively a spring chicken compared to me, but as Indiana jones observed, “It’s not the age, it’s the mileage.”

LikeLike